Indigenous Design: Considerations and Approach

Designers have the pleasure and privilege of working on diverse projects with unique clients, needs and requirements. Building a solid foundation for imagination and creativity to flourish involves extensive exploration, research, learning and collaboration. With accumulated knowledge, uncommon connections with different disciplines, cultures and fields can be made, bringing about amazing outcomes. In North America, designers have an exciting opportunity to serve people and communities with various cultural and heritage backgrounds. Co-creating private and public spaces that preserve their cultures and heritage in this modern age is a thrilling adventure.

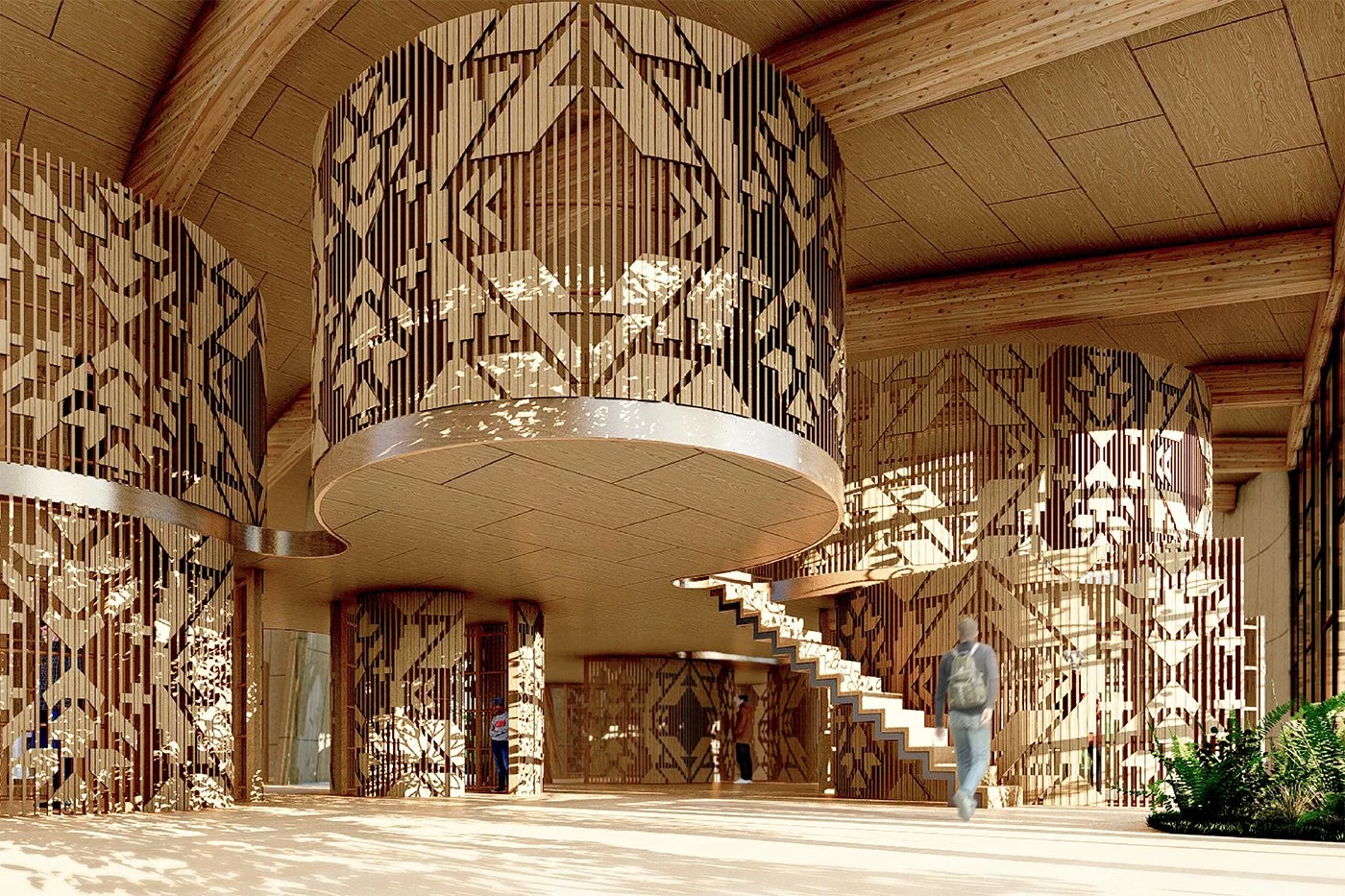

Tawaw Architecture Collective’s design for The Chippewa of the Thames First Nation Heritage Hub. Image courtesy of Tawaw Architecture Collective Inc.

Being a part of a project that serves Indigenous clients is not just an opportunity to strengthen my ties with the land that became my home but also a chance to expand my knowledge and understanding of the First Nations who have lived here and taken care of this land to foster deep connection and cooperation.

My work in wellbeing design has shown me that spaces profoundly shape how people feel, heal, and connect. Environmental psychology, biophilic design, and trauma-informed approaches all point to the same truth: we are deeply affected by our surroundings. This understanding resonates with Indigenous ways of knowing, which have long recognized the relationship between place, community, and wellbeing. What I bring to this work is not expertise in Indigenous culture, but a deep commitment to creating spaces where people feel they belong, are held, and can rest. This philosophy of making it feel home aligns naturally with Indigenous values of connection to land and community.

Approaching a design project for Indigenous people and communities asks for a deep understanding and respect for their cultural values, traditions, and way of life. As a non-Indigenous person, my first and most important attitude is to come in ready and willing to learn, listen, and even unlearn some of the practices I have applied to support non-Indigenous projects.

Here are some key considerations:

Cultural Sensitivity

The design process calls for cultural sensitivity and respect for Indigenous traditions, beliefs, and practices. This means engaging with the community and seeking their input and guidance throughout, not as consultation but as true collaboration.

Traditional Knowledge

Indigenous communities hold a deep understanding of their environment, sustainable practices, and traditional building techniques. This knowledge, passed through generations, offers wisdom that contemporary design is only beginning to rediscover. Working alongside community members and elders allows these elements to find their rightful place in the design.

Community Participation

When the community is involved in the design process, their needs and aspirations are genuinely reflected in the outcome. Workshops, community meetings, and design charrettes create opportunities for input and foster a sense of ownership and pride. This collaborative approach matters deeply. Spaces that support wellbeing emerge from understanding how people actually live, gather, and heal. That knowledge lives within the community, not in design manuals.

Sustainable Design

Sustainable design principles align beautifully with Indigenous values of stewardship and respect for the environment. Locally sourced materials, passive design strategies, and energy efficiency all honour this relationship with the land. Biophilic design, which brings nature into the built environment through natural light, materials, views, and living elements, supports both sustainability and human wellbeing. These principles are not new to Indigenous communities, who have always understood the importance of connection to the natural world.

Cultural Identity

Spaces that celebrate and reflect the community's cultural identity through traditional art, symbols, and motifs become places where culture is lived and passed on. They facilitate cultural practices, ceremonies, and gatherings. Environmental psychology tells us that spaces reflecting our identity and values reduce stress and support mental health. When people see themselves in their surroundings, they feel a sense of belonging that contributes to overall wellbeing.

Flexibility and Adaptability

Indigenous communities have dynamic and evolving needs. Flexible and adaptable spaces accommodate changing uses and functions over time, allowing the built environment to grow with the community rather than constraining it.

Collaboration with Indigenous Architects and Designers

Indigenous architects and designers bring deep understanding of the cultural context that cannot be learned from outside. Their expertise and leadership are essential. As a wellbeing design specialist, my role is to support and complement their vision, bringing what I know about how interior environments affect human experience while they lead on cultural direction and community relationships.

Respect for Sacred Spaces

Indigenous communities often have sacred sites and spaces holding spiritual significance. These require protection and preservation. Trauma-informed design principles are also relevant here. Many Indigenous communities carry the weight of historical trauma, and spaces designed for healing must acknowledge this reality. Environments that feel safe, that offer choice and control, and that support restoration honour this need.

Amazay Lake BC - Tse Keh Nay People - Picture curtesy Sacredland.org

Long-Term Sustainability

A project's long-term sustainability depends on thoughtful consideration of maintenance, operation, and ongoing community involvement. Capacity building, training, and local employment opportunities help ensure the project continues to serve the community for generations.

Accessibility and Inclusivity

Accessible and inclusive design welcomes all community members, including those with disabilities or mobility challenges. Universal design principles create spaces where everyone belongs.

Spaces That Support Healing

Research in environmental psychology consistently shows that the physical environment affects healing outcomes. Natural light, connection to outdoors, appropriate acoustics, and thoughtful material choices all contribute to how people feel and recover. Indigenous wellness centres, health facilities, and housing projects benefit from this knowledge. The goal is not to impose frameworks, but to bring technical expertise to bear in service of what communities want to create for themselves.

Each Indigenous community is unique, and each project asks for an open mind, willingness to learn, and respect for cultural heritage. What I offer is expertise in creating spaces that support human wellbeing, combined with humility about what I do not know. The intersection of wellbeing design and Indigenous design values feels natural to me. Both recognize that space is not neutral. Both understand that connection to place and community is essential to health. Both are about creating environments where people can thrive.

With Joy & Delight!